Blog Series & Interviews

A Rain of Blessings

Thekchen Choling’s Babette Teich-Visco investigates the mystery of Buddhist relics.

Toward the end of his life, Shakyamuni Buddha gathered 16 of his closest disciples and charged them with protecting and spreading his teachings. Although the disciples—known as arhats—died some 2,500 years ago, modern-day Buddhists are convinced that these ancient followers are still making good on their promise.

“The arhats agreed to spread the Dharma until the next buddha arrived,” says Babette Teich-Visco, president of Thekchen Choling Syracuse. “Much of their work presumably occurs in other realms, invisible to the naked eye.”

Of course, there are exceptions. Among the most intriguing ones are bodily relics—pearl-like objects found in the cremated remains of Buddhist masters. Babette explains that such relics are “physical manifestations” of holy people.

“Relics contain strong healing powers and can ward off evil,” she continues. “Just being in the presence of a relic can do immeasurable good. It can make you feel calm, peaceful, meditative and inspired.”

We recently caught up with Babette, who is curating a special exhibition at Thekchen Choling called A Rain of Blessings, Nov. 1-3. The display, which is part of the temple’s 10th anniversary celebrations, features more than two-dozen relics from the Historical Buddha and his 16 arhats.

How did Thekchen Choling Syracuse acquire the relics?

They were gifted to us by Singha Rinpoche [founder and spiritual director of the Thekchen Choling family of temples] over a span of several years, starting in 2014.

Except for an exhibition in 2019, our relics are rarely seen in their entirety. We have a small travel container of relics for blessings at hospitals, nursing homes, jails and animal shelters. Otherwise, the relics of Shakyamuni Buddha, housed in a small reliquary on our altar, are the only ones displayed year-round.

Where did they originally come from?

When the Buddha died around 480 B.C., his ashes were divided among eight kings. Some 200 years later, a famous Indian king named Ashoka acquired the relics and placed them in stupas that he had built throughout India and other parts of South Asia.

Some people claim Ashoka built 48,000 stupas, but the number was probably more like a few hundred. Relics of the Buddha and his arhats are especially rare, so to have some in our temple is a huge blessing.

How did you become interested in relics?

I guess I’ve always been fascinated by them. This interest led to my involvement with the Maitreya Loving Kindness Relic Tour, a multinational exhibition of ancient and sacred objects that ran from 2001-15.

The relics we’re presenting here are called ringsel in Tibetan or sarira in Sanskrit. They defy scientific explanation because of their ability to self-propagate and sometimes emit light. I recall an incident a few years ago in which I went to our relics container and noticed that two relics had manifested on their own, along with hundreds of what looked like tiny drops of nectar. I was surprised and more than a little curious.

What does science have to say about this?

Nothing conclusive. Scientists argue that the human body contains chemicals that when exposed to extreme heat, like cremation, can produce interesting objects. But that doesn’t explain how relics can be luminous or propagate on their own after centuries of cooling.

The great Buddhist scholar and meditator, Lama Zopa Rinpoche, believed that because of impure karma and lack of merit, most people cannot see or hear the divine. Thus, the Buddha and his disciples emanated thousands of relics for us to use as objects of devotion. They’re blessings of the body, speech and mind.

Are there different kinds of relics?

Ringsel crystals are most common, but bone, tooth and hair exist in small quantities. The Buddha Tooth Relic Temple and Museum in Singapore is world-famous because it houses his left canine. The tooth, which was recovered from the Buddha’s funeral pyre in India, is still growing.

Other types of Buddhist relics include personal possessions, like parts of a robe, staff or handwritten letter.

What do you hope people get out of A Rain of Blessings?

This showing is a special opportunity for not only Thekchen Choling Syracuse, but also the greater community. Whether you’re a student, scholar, teacher or practitioner of Buddhism—or even a skeptic—you’re bound to be affected by the collection. I’ve seen, with my own eyes, the impact they have on people.

To the untrained eye, a relic looks like an ordinary pearl or opal. To someone on the path to enlightenment, it’s the promise of infinite blessing.

Editor’s Note: A Rain of Blessings will be accompanied by interactive activities, like Heart Sutra copying, a baby Buddha bathing ritual, a meditation-for-beginners class and a Guru Puja ceremony.

When not sitting and meditating among the relics, attendees are encouraged to watch loop videos about the life of the Buddha and how Singha Rinpoche acquired the relics. Program guides are available for $15.

Blurring the Edges

Holistic healthcare practitioner Diana Macchiavelli discusses the universal appeal of Chinese medicine.

Diane Macchiavelli, L.Ac, has devoted the past 50 years to exploring Chinese medicine and Tibetan Buddhism. So when she recently asked Jhado Rinpoche how to improve her practice, he responded with sage advice from Shakyamuni Buddha: “Don’t rush anything. When the time is right, it will happen.”

For all her credentials and decades of training and practice, Macchiavelli, 73, still considers herself a beginner. “We never stop learning because life never stops teaching us,” she says, speaking by phone from her wellness clinic, Brighton Pathways to Health, in Rochester, New York. “Jhado Rinpoche reminded me to slow down and take the long view but also pay attention to each moment.”

A longtime supporter of Thekchen Choling Syracuse, Macchiavelli returns to the Minoa-based temple to lead healing workshops on Saturday, July 13. “The morning session is called Radiant Mind and is fairly didactic, looking at how Five-Element Theory can be applied to our daily lives,” she says. “The afternoon program is titled Active Body. We’ll do QiGong and T’ai Chi, followed by a special guided meditation.”

We recently caught up with Macchiavelli to discuss her lifelong pursuit of health and wellness—and learning.

What exactly is “Chinese medicine”?

Chinese medicine means different things to different people. My focus is on an ancient system that takes a mind-body-spirit approach to healing.

A common metaphor for Chinese medicine is the “check engine” light in your car. When it comes on, you get a signal that something is wrong. But you don’t fix the problem by cutting the wire to the light or changing the lightbulb. Instead, you run a diagnostic test to identify the root cause of the symptom.

In Chinese medicine, pain is our “check engine” light. It indicates something is out of whack, that we need to get to the cause of the problem. The approach is holistic, not symptomatic.

How is Five-Element Theory involved?

The Chinese believe that everything on our physical, earthly plane comes from five elements: wood, fire, earth, metal and water. The elements affect our health by interacting with one another. They also influence interpersonal relationships and organizational behavior.

Medical practitioners discovered long ago that the elements correspond to different organ systems and their functions. Each element also is associated with a color, a sound, an odor and an emotion. Because health is an expression of each element, it’s important to determine which elements are functioning properly and which ones aren’t. This information is used to create a holistic treatment plan.

Sounds like a constant balancing act.

It is. For instance, fire is an element that’s associated with summer. If you look at our natural word and, specifically, global warming, you see intense rainfall and flooding. This is Mother Earth’s way of restoring equilibrium by increasing the presence of water. Water puts out fire.

On a human level, the Fire Element, when out of balance, can lead to overexcitement and an excess of desire and activity. We can address such imbalances by making informed decisions about nutrition and exercise. We eat warming or cooling foods. We engage in activities that calm or excite us. There are also acupuncture points on the body that are associated with the Fire Element.

The Law of “Mother-Child Relationship” is one way to describe this process. In the cycle of the Five Elements, each element is the “child” of the “mother” producing it. If we look at the Wood Element, we see that it’s the “mother” of the Fire Element and the “child” of Water.

What does Five-Element Theory have to with QiGong and T’ai Chi?

Five-Element Theory explains how energy flows to and from the 12 organs. The Chinese call this subtle breath energy qi [pronounced “chee”]. Qi originates in the kidneys, which, in turn, filter blood circulating throughout the body.

Sometimes, our qi gets stuck. Movement therapy, like Qigong and T’ai Chi, releases these blockages and restores the flow of energy.

What’s the difference between T’ai Chi and Qigong?

T’ai Chi is a series of postures linked by flowing movements. Also known as Chinese Yoga, T’ai Chi is highly restorative. I’ve seen it work wonders on people living with an illness like Parkinson’s disease or recovering from a stroke or sports injury.

Qigong is also restorative but focuses on one repetitive movement at a time.

Are T’ai Chi and Qigong specific to Buddhism?

They’re nonreligious, so people from all backgrounds can practice them. This is because the “life force” is a universal concept. The Chinese refer to it as qi. The Japanese call it ki [pronounced “key”]. It’s prana to those who practice traditional Indian systems, like yoga or Ayurvedic medicine. That’s what I love about my work—it blurs the edges.

How did you become interested in Chinese medicine?

I’ve always been curious and open-minded. I discovered Taoism and Buddhism as an art student at the University of Maryland, College Park. I subsequently embarked on specialized training in the United States and abroad. One of my primary teachers was Robert W. Smith, who helped introduced T’ai Chi to the West after World War II.

What do you hope to accomplish at Thekchen Choling on July 13?

Each of us tends to label things and then put them in boxes. Western medicine is no different with its emphasis on identifying and treating symptoms. As a result, there’s a certain amount of myth-busting I do to help people see the bigger picture. Chinese medicine supports the idea that by tending to our mind, body and spirit, we can enhance our overall health and wellness.

Recent studies show that it takes approximately 10,000 years for physical changes to occur in our bodies. These changes impact our mental and spiritual health. I’m grateful for organizations like Thekchen Choling Syracuse, which, through events like this one, help people navigate these changes—to learn how to become whole and have purpose in life.

Following the Path of the Buddha

Earlier this year, sangha member Sarah Davis embarked on the journey of a lifetime, exploring the exotic culture and wonder of Vietnam and Cambodia. Here are a few snapshots from her bucket-list trip.

In January, I visited two UNESCO World Heritage sites: Angkor Wat, the world’s largest religious structure, located in Cambodia, and Bai Dinh, a vast Buddhist temple complex in Vietnam.

Occupying some 400 acres, Angkor Wat comprises more than a thousand ancient Hindu-Buddhist buildings. They include five central towers representing Mount Meru, long considered the center of the spiritual and physical universes.

The author at Angkor Wat at sunrise. The towers symbolize Cambodia’s Mount Meru.

A radical communist group beheaded most of the original Buddhist statues in the 1990s. The heads were sold with whole statues and other antiquities to buy firearms.

A headless Buddha statue at Angkor Wat.

Many of Angkor Wat’s cylindrical lingas, representing the Hindu god Shiva, remain intact.

A lingua is an abstract representation of Shiva.

Bai Dihn is another major cultural destination. The complex contains a 900-year-old pagoda as well as one built in 2003. Bai Dihn also houses the largest, gold-plated, bronze Buddha statue in Southeast Asia and the biggest bronze bell in Vietnam.

The new Bai Dihn Pagoda in Vietnam.

The main hall of Bai Dihn Pagoda contains the biggest bronze Buddha statue in Southeast Asia.

It was the non-touristry offshoots—quiet pagodas and mountain caverns—that most appealed to me. They presented opportunities for solitude and reflection. I can’t wait to return.

Ao Giai Lake in Bai Dihn is known for its green color all year round.

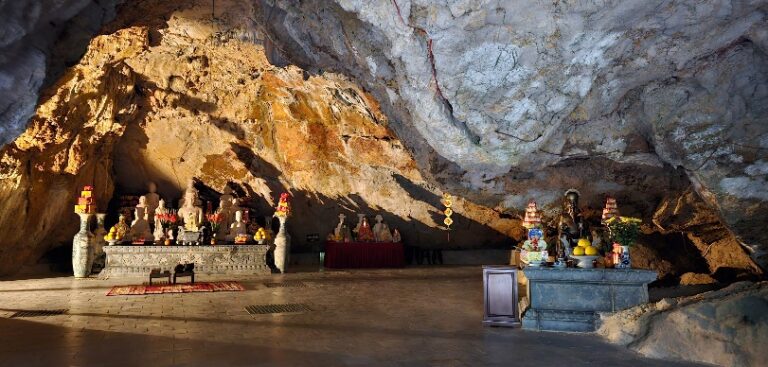

Formerly a prison, Am Tien Cave is part of the Bai Dihn pagoda complex.

The Way of the Boddhisattva

Babette Teich-Visco announces a new weekly course on the Shantideva classic.

Little is known about the eight-century Indian philosopher Shantideva, aside from some colorful legends and half-truths. But one thing is for certain, says Babette Teich-Visco, president of Thekchen Choling Syracuse: “He was a special being.”

Although he was often misunderstood, Shantideva wielded a powerful intelligence combined with a deep understanding of the sufferings of the world. At Nalanda (a major university that flourished between the 7th-12th centuries), he drew the ire of his fellow monks by rarely studying for or attending class. “His apathy was a superpower in disguise,” Teich-Visco surmises.

It was at Nalanda that Shantideva delivered one of the great religious teachings of all time: The Way of the Boddhisattva. A monument in the Mahayana Buddhist tradition, the 900-verse poem lays out the methods by which one becomes a bodhisattva, vowing to help others.

Every Wednesday from 7-8:15 p.m., Thekchen Choling Syracuse hosts a reading and discussion group of the Shantideva classic. The event is free and open to the public. No knowledge of or experience with Buddhism is required.

“It takes about five years for us to go through the book,” says Teich-Visco, who discovered the text about 20 years ago. “People come, and people go, but along the way, unique relationships are formed with one another—and with the text, which is nothing short of miraculous.”

We recently caught up with Teich-Visco to discuss Shantideva’s landmark teaching.

Who was Shantideva?

He was a Buddhist monk, philosopher and poet who lived about 1,200 years ago. Like Shakyamuni Buddha before him, Shantideva was born into royalty but renounced everything to become a simple monk.

Scholars believe that Shantideva spent most of his life at Nalanda [monastery] in eastern India, mainly studying Mahayana Buddhism. [Mahayana is one of two primary branches of Buddhism. The other is Theravada, an older, more conservative religious system.] Initially, Shantideva was not well liked because he was notoriously lazy. His classmates joked that his three great “realizations” were eating, sleeping and shitting.

How did The Way of the Bodhisattva come about?

As the story goes, some monks tried to shame Shantideva into leaving Nalanda by asking him to give a public teaching. On the appointed day, he took his place on the teaching throne and asked everyone what they wanted to hear—something well known or something brand new. Hoping that he’d embarrass himself, members of the audience requested the latter. But what came out of Shantideva’s mouth was The Way of the Boddhisattva.

What else do we know about the event?

It’s shrouded in mystery, like most of Shantideva’s life. Some monks reported seeing the celestial bodhisattva Manjushri overhead while Shantideva taught. Others said that he and Manjushri disappeared into the night sky during the lesson on wisdom, but that Shantideva’s voice remained audible.

Because there were various accounts of the experience, Shantideva was sought out, years later, to confirm the definitive language. He also acknowledged the existence of two other original texts that were hiding in his meditation hut at Nalanda. Only one of them has survived: The Compendium of Training.

What’s important about The Way of the Bodhisattva?

It’s the foundation of Mahayana Buddhism. Whereas Mahayana is Sanskrit for the “Great Vehicle,” a bodhisattva is a “follower of the Great Vehicle”—specifically, someone who vows to work for the liberation of all beings.

Also, bodhisattva shouldn’t be confused with bodhicitta, which refers to an “awakened mind.” To be clear, bodhicitta is a defining quality; it’s what makes a bodhisattva a bodhisattva.

There are several English translations of The Way of the Bodhisattva. Ours was published about 25 years ago and revised in 2006. It contains 10 chapters that are divided into three sections: The Dawn of Bodhicitta; Protecting and Maintaining Bodhicitta; and Intensifying Bodhicitta, which includes a lengthy section on wisdom. The tenth and final chapter is a prayer of dedication.

The Way of the Bodhisattva is like a personal meditation. I consider it a how-to guide for cultivating bodhicitta. The language is beautiful, poetic and timeless.

Do you consider it a radical practice?

Absolutely. Compassionate living requires great wisdom and self-discipline. It can’t be done in isolation. The path of the bodhisattva flies in the face of today’s excessive individualism.

Even His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama considers The Way of the Boddhisattva relevant and useful. He credits the text for helping him understand both compassion and the practice of the bodhisattva path.

What might we expect from the course?

Each one is facilitated by our resident teacher, Geshe Lharampa Thinley Namgyal, who invites us to read, ruminate and discuss the text. It’s the attendees, however, who do most of the talking.

On average, we cover about a half dozen verses per session. While being Buddhist helps, it’s not required nor expected. Some of our most spirited discussions often involve those with little or no understanding of the dharma. Buddhism is not about blind faith; rather, it’s confidence based on study and meditation.

Any advice for attendees?

I’ve been working with The Way of the Bodhisattva for years. Like all Buddhists texts, it should be read slowly and repeatedly for maximum benefit. The process is a journey, not a race.

Babette Teich-Visco, president of Thekchen Choling Syracuse, with Khensur Jhado Tulku Rinpoche.

The Art of Dharma, the Dharma of Art

Painter Thomas Edwards finds inspiration—and fulfillment—in an ancient Tibetan Buddhist art form.

According to Tibetan lore, several artists were once commissioned to create a portrait of Shakyamuni Buddha. But no sooner had they begun painting than they were blinded by the light of his presence. “The artists finished the work by observing the Buddha’s reflection in a nearby body of water,” says Thomas Edwards, a professional Tibetan Buddhist artist. “They captured not only his image, but also his spirit.”

The result was arguably the first example of Thangka painting—a specialized type of Buddhist art that later caught fire in 11th-century Tibet.

Edwards, who resides in Cortland, New York, is one of today’s leading purveyors of Thangka art. Over the past two decades, he’s produced about a thousand Thangka paintings, many of which have been commissioned. Common among all of them is the reverent depiction of a great Buddhist deity.

“I’m living out my dreams,” says the practicing Tibetan Buddhist. “Thangka painting is my path to joy, purpose and meaning.”

We recently caught up with Edwards, who’s presenting a Thangka painting workshop at Thekchen Choling Syracuse, June 7-9, to discuss the art of self-realization.

What is Thangka painting?

Thangka is Tibetan for “recorded message.” Originally applied to the walls of caves and monasteries, these paintings have since been created on vertical scrolls of cotton fabric. Their portability has contributed to their popularity.

Thangka paintings metaphorically illustrate life as perceived from an enlightened state of mind. They aid in transcending limited egoic perspective, awakening enlightened perspective and living.

Because they’re tools for teaching, meditation and worship, Thangka paintings follow strict geometric guidelines, proportions and measurements. Forget what you know about traditional fine art; the rules don’t apply here.

Would you elaborate?

Thangka paintings depict enlightened beings, so they don’t show the effects of light, shadow and perspective. These paintings also use five primary colors, representing the five aspects of enlightened awareness and the five paths to such awareness.

White symbolizes purity and clarity. Red is associated with vigor, determination and magnetism. Yellow represents transcendent wisdom, joy and wisdom. Green typifies fearlessness and rejuvenation. And blue embodies inner power, ultimate reality and harmony.

Thangka paintings are made from top to bottom, beginning with the area furthest away from me. I don’t sign my pieces because doing so is considered an egocentric act.

“Thangka painting is my path to joy, purpose and meaning,” says Thomas Edwards, who has produced about a thousand such paintings.

How long does it take to make such a painting?

Usually one to two months, but I’ve made some medium-sized pieces [i.e., 17 x 20 inches] in less than a week. The standards are exacting. I use natural paints made from earth minerals and stone powers. Animal glue is a great [paint] binder.

Have you always been interested in art?

As a kid, I loved picture books and encyclopedias, especially ones with fantastical illustrations of Hindu deities and mythological scenes. I was 13 or 14 years old when I began studying Buddhism and became obsessed with the colorful depictions of gods and goddesses.

I’ve made several trips to Dharamsala [home of His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama in northern India] to study Buddhist art. My teachers have included such Tibetan masters as Tenzin Ngodup and Migmar Tsering, both of whom studied under the late Sangye Yeshe, the Dalai Lama’s personal Thangka painter.

What’s unique about your approach?

I work in a classical, or traditional, style, which is rarely taught these days. I lay out every painting with a grid. This method determines the size and placement of visual elements. Only after the sketch is inked do I begin painting it with a fine brush.

Thangka painting is a long, painstaking process. Nothing is left to chance. It’s informed by my understanding of Buddhist scriptures and iconography.

Is there more to Thangka painting than meets the eye?

Each painting houses the spirits of deities, revealing hidden dimensions of the truth. It’s also infused with sacred geometry, in which shapes carry different spiritual meanings—something for which Leonard da Vinci is also known. There’s a strange, mysterious elegance to it.

Thangka painting is like mantra chanting—a form of meditation and spiritual dialogue. My process is empowered by and activated with prayer, invocation and crystallized blessings of the recited relevant mantra. Each brushstroke is encoded with a frequency, or vibration, that awakens my higher mind. It’s my dharma.