Blog Series & Interviews

Following the Path of the Buddha

Earlier this year, sangha member Sarah Davis embarked on the journey of a lifetime, exploring the exotic culture and wonder of Vietnam and Cambodia. Here are a few snapshots from her bucket-list trip.

In January, I visited two UNESCO World Heritage sites: Angkor Wat, the world’s largest religious structure, located in Cambodia, and Bai Dinh, a vast Buddhist temple complex in Vietnam.

Occupying some 400 acres, Angkor Wat comprises more than a thousand ancient Hindu-Buddhist buildings. They include five central towers representing Mount Meru, long considered the center of the spiritual and physical universes.

The author at Angkor Wat at sunrise. The towers symbolize Cambodia’s Mount Meru.

A radical communist group beheaded most of the original Buddhist statues in the 1990s. The heads were sold with whole statues and other antiquities to buy firearms.

A headless Buddha statue at Angkor Wat.

Many of Angkor Wat’s cylindrical lingas, representing the Hindu god Shiva, remain intact.

A lingua is an abstract representation of Shiva.

Bai Dihn is another major cultural destination. The complex contains a 900-year-old pagoda as well as one built in 2003. Bai Dihn also houses the largest, gold-plated, bronze Buddha statue in Southeast Asia and the biggest bronze bell in Vietnam.

The new Bai Dihn Pagoda in Vietnam.

The main hall of Bai Dihn Pagoda contains the biggest bronze Buddha statue in Southeast Asia.

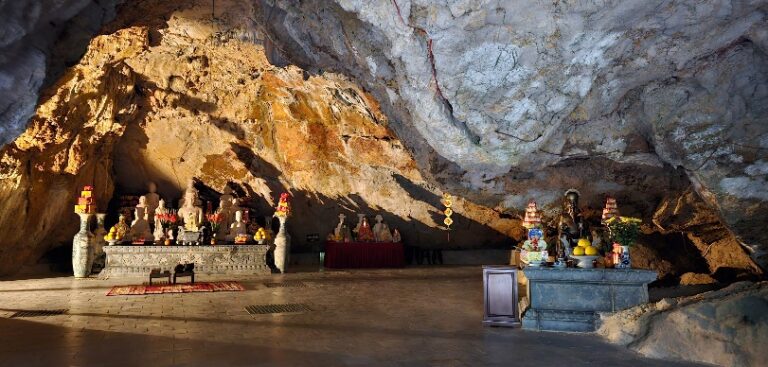

It was the non-touristry offshoots—quiet pagodas and mountain caverns—that most appealed to me. They presented opportunities for solitude and reflection. I can’t wait to return.

Ao Giai Lake in Bai Dihn is known for its green color all year round.

Formerly a prison, Am Tien Cave is part of the Bai Dihn pagoda complex.

The Way of the Boddhisattva

Babette Teich-Visco announces a new weekly course on the Shantideva classic.

Little is known about the eight-century Indian philosopher Shantideva, aside from some colorful legends and half-truths. But one thing is for certain, says Babette Teich-Visco, president of Thekchen Choling Syracuse: “He was a special being.”

Although he was often misunderstood, Shantideva wielded a powerful intelligence combined with a deep understanding of the sufferings of the world. At Nalanda (a major university that flourished between the 7th-12th centuries), he drew the ire of his fellow monks by rarely studying for or attending class. “His apathy was a superpower in disguise,” Teich-Visco surmises.

It was at Nalanda that Shantideva delivered one of the great religious teachings of all time: The Way of the Boddhisattva. A monument in the Mahayana Buddhist tradition, the 900-verse poem lays out the methods by which one becomes a bodhisattva, vowing to help others.

Every Wednesday from 7-8:15 p.m., Thekchen Choling Syracuse hosts a reading and discussion group of the Shantideva classic. The event is free and open to the public. No knowledge of or experience with Buddhism is required.

“It takes about five years for us to go through the book,” says Teich-Visco, who discovered the text about 20 years ago. “People come, and people go, but along the way, unique relationships are formed with one another—and with the text, which is nothing short of miraculous.”

We recently caught up with Teich-Visco to discuss Shantideva’s landmark teaching.

Who was Shantideva?

He was a Buddhist monk, philosopher and poet who lived about 1,200 years ago. Like Shakyamuni Buddha before him, Shantideva was born into royalty but renounced everything to become a simple monk.

Scholars believe that Shantideva spent most of his life at Nalanda [monastery] in eastern India, mainly studying Mahayana Buddhism. [Mahayana is one of two primary branches of Buddhism. The other is Theravada, an older, more conservative religious system.] Initially, Shantideva was not well liked because he was notoriously lazy. His classmates joked that his three great “realizations” were eating, sleeping and shitting.

How did The Way of the Bodhisattva come about?

As the story goes, some monks tried to shame Shantideva into leaving Nalanda by asking him to give a public teaching. On the appointed day, he took his place on the teaching throne and asked everyone what they wanted to hear—something well known or something brand new. Hoping that he’d embarrass himself, members of the audience requested the latter. But what came out of Shantideva’s mouth was The Way of the Boddhisattva.

What else do we know about the event?

It’s shrouded in mystery, like most of Shantideva’s life. Some monks reported seeing the celestial bodhisattva Manjushri overhead while Shantideva taught. Others said that he and Manjushri disappeared into the night sky during the lesson on wisdom, but that Shantideva’s voice remained audible.

Because there were various accounts of the experience, Shantideva was sought out, years later, to confirm the definitive language. He also acknowledged the existence of two other original texts that were hiding in his meditation hut at Nalanda. Only one of them has survived: The Compendium of Training.

What’s important about The Way of the Bodhisattva?

It’s the foundation of Mahayana Buddhism. Whereas Mahayana is Sanskrit for the “Great Vehicle,” a bodhisattva is a “follower of the Great Vehicle”—specifically, someone who vows to work for the liberation of all beings.

Also, bodhisattva shouldn’t be confused with bodhicitta, which refers to an “awakened mind.” To be clear, bodhicitta is a defining quality; it’s what makes a bodhisattva a bodhisattva.

There are several English translations of The Way of the Bodhisattva. Ours was published about 25 years ago and revised in 2006. It contains 10 chapters that are divided into three sections: The Dawn of Bodhicitta; Protecting and Maintaining Bodhicitta; and Intensifying Bodhicitta, which includes a lengthy section on wisdom. The tenth and final chapter is a prayer of dedication.

The Way of the Bodhisattva is like a personal meditation. I consider it a how-to guide for cultivating bodhicitta. The language is beautiful, poetic and timeless.

Do you consider it a radical practice?

Absolutely. Compassionate living requires great wisdom and self-discipline. It can’t be done in isolation. The path of the bodhisattva flies in the face of today’s excessive individualism.

Even His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama considers The Way of the Boddhisattva relevant and useful. He credits the text for helping him understand both compassion and the practice of the bodhisattva path.

What might we expect from the course?

Each one is facilitated by our resident teacher, Geshe Lharampa Thinley Namgyal, who invites us to read, ruminate and discuss the text. It’s the attendees, however, who do most of the talking.

On average, we cover about a half dozen verses per session. While being Buddhist helps, it’s not required nor expected. Some of our most spirited discussions often involve those with little or no understanding of the dharma. Buddhism is not about blind faith; rather, it’s confidence based on study and meditation.

Any advice for attendees?

I’ve been working with The Way of the Bodhisattva for years. Like all Buddhists texts, it should be read slowly and repeatedly for maximum benefit. The process is a journey, not a race.

Babette Teich-Visco, president of Thekchen Choling Syracuse, with Khensur Jhado Tulku Rinpoche.

The Art of Dharma, the Dharma of Art

Painter Thomas Edwards finds inspiration—and fulfillment—in an ancient Tibetan Buddhist art form.

According to Tibetan lore, several artists were once commissioned to create a portrait of Shakyamuni Buddha. But no sooner had they begun painting than they were blinded by the light of his presence. “The artists finished the work by observing the Buddha’s reflection in a nearby body of water,” says Thomas Edwards, a professional Tibetan Buddhist artist. “They captured not only his image, but also his spirit.”

The result was arguably the first example of Thangka painting—a specialized type of Buddhist art that later caught fire in 11th-century Tibet.

Edwards, who resides in Cortland, New York, is one of today’s leading purveyors of Thangka art. Over the past two decades, he’s produced about a thousand Thangka paintings, many of which have been commissioned. Common among all of them is the reverent depiction of a great Buddhist deity.

“I’m living out my dreams,” says the practicing Tibetan Buddhist. “Thangka painting is my path to joy, purpose and meaning.”

We recently caught up with Edwards, who’s presenting a Thangka painting workshop at Thekchen Choling Syracuse, June 7-9, to discuss the art of self-realization.

What is Thangka painting?

Thangka is Tibetan for “recorded message.” Originally applied to the walls of caves and monasteries, these paintings have since been created on vertical scrolls of cotton fabric. Their portability has contributed to their popularity.

Thangka paintings metaphorically illustrate life as perceived from an enlightened state of mind. They aid in transcending limited egoic perspective, awakening enlightened perspective and living.

Because they’re tools for teaching, meditation and worship, Thangka paintings follow strict geometric guidelines, proportions and measurements. Forget what you know about traditional fine art; the rules don’t apply here.

Would you elaborate?

Thangka paintings depict enlightened beings, so they don’t show the effects of light, shadow and perspective. These paintings also use five primary colors, representing the five aspects of enlightened awareness and the five paths to such awareness.

White symbolizes purity and clarity. Red is associated with vigor, determination and magnetism. Yellow represents transcendent wisdom, joy and wisdom. Green typifies fearlessness and rejuvenation. And blue embodies inner power, ultimate reality and harmony.

Thangka paintings are made from top to bottom, beginning with the area furthest away from me. I don’t sign my pieces because doing so is considered an egocentric act.

“Thangka painting is my path to joy, purpose and meaning,” says Thomas Edwards, who has produced about a thousand such paintings.

How long does it take to make such a painting?

Usually one to two months, but I’ve made some medium-sized pieces [i.e., 17 x 20 inches] in less than a week. The standards are exacting. I use natural paints made from earth minerals and stone powers. Animal glue is a great [paint] binder.

Have you always been interested in art?

As a kid, I loved picture books and encyclopedias, especially ones with fantastical illustrations of Hindu deities and mythological scenes. I was 13 or 14 years old when I began studying Buddhism and became obsessed with the colorful depictions of gods and goddesses.

I’ve made several trips to Dharamsala [home of His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama in northern India] to study Buddhist art. My teachers have included such Tibetan masters as Tenzin Ngodup and Migmar Tsering, both of whom studied under the late Sangye Yeshe, the Dalai Lama’s personal Thangka painter.

What’s unique about your approach?

I work in a classical, or traditional, style, which is rarely taught these days. I lay out every painting with a grid. This method determines the size and placement of visual elements. Only after the sketch is inked do I begin painting it with a fine brush.

Thangka painting is a long, painstaking process. Nothing is left to chance. It’s informed by my understanding of Buddhist scriptures and iconography.

Is there more to Thangka painting than meets the eye?

Each painting houses the spirits of deities, revealing hidden dimensions of the truth. It’s also infused with sacred geometry, in which shapes carry different spiritual meanings—something for which Leonard da Vinci is also known. There’s a strange, mysterious elegance to it.

Thangka painting is like mantra chanting—a form of meditation and spiritual dialogue. My process is empowered by and activated with prayer, invocation and crystallized blessings of the recited relevant mantra. Each brushstroke is encoded with a frequency, or vibration, that awakens my higher mind. It’s my dharma.