Tibetan yoga at tccl

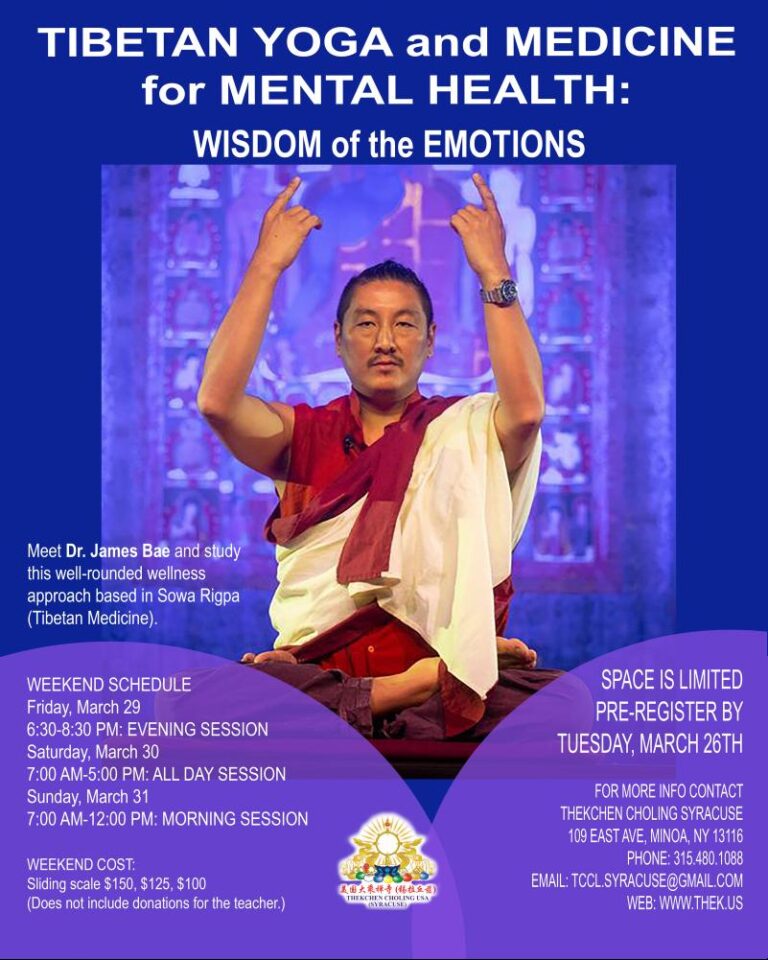

Yoga Therapist James Bae to Explore Buddhist Approach to Mental Health March 29-31

Weekend retreat at Thekchen Choling Syracuse will provide tools and insights for health and wellness.

Renowned yoga therapist and educator James Bae returns to Central New York to lead a hands-on weekend retreat. Titled “Tibetan Yoga and Medicine for Mental Health: Wisdom of the Emotions,” the program will take place at Thekchen Choling Syracuse (109 East Ave., Minoa) on March 29-31. Space is limited.

For more information, including cost ($100-$150), food and lodging, visit thekchencholingus.com or email tccl.syracuse@gmail.com. The deadline for registration, which is required, is midnight (ET) on Tuesday, March 26.

Babette Teich-Visco, president of the Syracuse-based Buddhist temple, considers Bae’s visit timely and relevant. “Everyone is struggling to cope with an increasingly complex world. James Bae offers a solution—time-honored practices that bring your energies back into balance, enabling you to live a happy, healthy life.”

Open to people of all ages, backgrounds and physical abilities, the retreat will explore meditation, yogic breathwork, and movement and mantra practices for mental health and physical well-being.

Attendees also will uncover Tibetan medical approaches to detoxification and rejuvenation and consider how emotional and stress regulation affects health and longevity.

“We’ll offer lots of practical methods for self-healing through yoga, diet, herbs and self-massage,” says Teich-Visco, adding that Bae is a proponent of Sowa-Rigpa, an ancient Buddhist medical system focusing on the body, mind and spirit. “Healthcare providers will particularly benefit.”

Bae is no stranger to Central New York, having led a sold-out retreat at Thekchen Choling Syracuse last summer. A doctor of Chinese medicine, he has more than two decades of Tibetan, Indian and Japanese medicine under his belt.

“I take an evidenced-based approach to mind-body and self-care practices,” says the globe-trotting yogi, who also is a certified yoga therapist and educator, a trauma-informed care provider, and the owner of a thriving acupuncture studio in Brooklyn. Bae will lead another retreat at Thekchen Choling Syracuse in August (dates TBA).

Other upcoming presenters include Thomas Edwards, a traditional Tibetan Buddhist Thangka painter, and Diane Macchiavelli, who specializes in traditional Five Element acupuncture. Stay tuned for details.

Thekchen Choling Syracuse is part of Thekchen Choling, a Buddhist temple with branches in Singapore and Malaysia. Celebrating its 10th anniversary this fall, the Syracuse-based organization offers programs and activities and houses many precious Buddhist relics.

Fire Down Below

Yoga therapist and educator James Bae explores the mystical connection between tummo and ancient Tibetan yoga.

As a promising researcher in his twenties, James Bae would read up to 40 books a week. “I taught myself how to speed-read,” says the noted authority on Tibetan yogic practices. “Once I picked up a book, I couldn’t put it down, and this immensely helped my understanding of yoga and medicine.”

Today, the eloquent, globe-trotting yogi still honors his bookish Jersey roots but prefers putting theory into practice. Founder of a thriving acupuncture studio in Brooklyn, Bae draws on more than two decades of experience in Indian, Tibetan, Japanese and Chinese medicine. “I take an evidenced-based approach to mind-body and self-care practices,” says the certified yoga therapist and educator, who also is a trauma-informed care-provider. “Because the medical and contemplative studies fields are always changing, my work is always changing.”

Writer Rob Enslin (RE) recently caught up with Bae (JB) in Central New York, where the latter led a weekend Lu Jong retreat at Thekchen Choling Syracuse. “Lu Jong is an ancient Tibetan healing yoga that simultaneously works the body, mind and energy,” says Bae, who earned a doctoral degree in medical science from the American College of Traditional Chinese Medicine in San Francisco. “It’s central to what I do as a doctor of Chinese medicine.”

They were joined by Babette Teich-Visco (BTV), the temple’s president and acting director, who queried Bae about his involvement with tummo, a temperature-raising practice that combines breathing and visualization techniques. “We hit it hard, Jersey-style,” Bae joked afterward, regarding teaching such a rigorous, timeless discipline.

RE: Was there a single moment that set the stage for what you’re doing now, or was the evolution gradual?

JB: I grew up in a Buddhist household where I was introduced to almost everything I do today, including acupuncture. Of course, I rebelled and studied every other [medical] tradition until I realized what I had suspected all along—that the Chinese medical system is good for integrative medicine, licensure and clinical work.

RE: What do you think about the mainstreaming of yoga?

JB: There’s value to the influence of yoga on contemporary culture. At the same time, people should seek to understand its deeper meaning so that they can contextualize yoga to reap its full benefits.

RE: Would you elaborate?

JB: Indian traditions of yoga, meditation and asceticism are rich and diverse, but only through academic research have we begun to understand their history. For instance, scholars have discovered that classical Indian yoga was profoundly influenced by Buddhist culture. And contrary to popular belief, Hatha yoga [which uses physical techniques to preserve and channel one’s vital energy] was allied to Buddhist tradition.

I used to study with Georg Feuerstein, who wrote more than 40 books on yoga. Even though he was a highly regarded scholar of Classical Indian Yoga, his belief that yoga underscored not one tradition, but multiple ones—Buddhism, Jainism and to some degree, Daoism and Hinduism—was controversial. Scholars are beginning to realize that Georg was right to some degree.

BTV: Tummo breathing is a major part of your teaching and practice. Why has it become so popular?

JB: It’s a mind-body practice that cultivates wisdom and promotes healing. In the West, there’s a predicament of disembodiment—that we rarely feel our emotions because we live in our heads all the time. As a result, we don’t know how to respond to or be present to things happening around us, even if they’re related to something that happened to us a long time ago.

Somatic approaches like tummo help us to realize our dharma more fully—to be in our bodies more.

BTV: Can it make you a better Buddhist?

JB: Tummo, when used in conjunction with the Threefold Way of ethics, meditation and wisdom, can lead to a deeper understanding of emptiness. It’s the most direct method for experiencing your deepest inner nature.

Because it possesses such value and power, tummo has long been held in secrecy in India and Tibet, where it’s reserved for only initiates. That said, the tradition is slowly spreading to the West.

BTV: What advice do you have for contemporary tummo practitioners?

JB: It’s a great way to face suffering head on, provided there are safeguards in the teacher-student relationship. A good teacher can provide care for and guidance with the tradition. They can also help with ethical development—virtues promoting happiness, good merit and right action.

RE: How do you define emptiness?

JB: A central concept of Tibetan Buddhism is sahaja, or spontaneous enlightenment. Whatever else you call it—emptiness, luminosity, clear light experience—it’s the process by which you achieve oneness with divine, inner nature.

Everyone encounters oneness at death. But with proper training, we can also experience it while we’re alive, bringing tremendous benefit to ourselves and others. It’s also a source of well-being.

RE: How can teachers and gurus help us?

JB: A teacher usually works with a student for a set period, sharing skills and knowledge, whereas a guru is for life—and beyond—imparting wisdom and self-realization. These kinds of people check your experience. They want to know where your wisdom is coming from and if it’s grounded. They use a system of checks and balances to keep us honest. And humble.

RE: Humble?

JB: Absolutely. You can’t imagine what they’ve seen or heard or what they have learned from their own teachers. The training that Tibetan Buddhists endured only two generations ago, along with their cultural and lived experiences, is practically unfathomable today.

That’s why the notion of lineage, in which the Buddha’s teachings are transmitted from one generation to the next, is vitally important. Technology, if used properly, can advance our understanding and practice of Tibetan Buddhism in a profound way.

BTV: How do retreats reinforce the idea of lineage?

JB: Serving a lineage is an opportunity to serve your teacher. It’s a personal thing. I don’t go looking for students, and I’m certainly not into adulation. But whenever I lead a retreat or a workshop, I envision my teacher above my head. I see you in front of me, but I am reminded of him. It’s really moving.

BTV: Why is intention important?

JB: When you serve a lineage, you’re tapping into an aspiration that’s been held for generations. A good teacher is someone who cares for you—who’s willing to take you aside and show you what kindness and compassion can really do for you.

Intention can make you go from country to country, like I do, and basically invite people to dance. I want you to come alive. And I want you to see yourself come alive.

RE: It seems like the Buddha’s teachings are not just relevant; they’re also practical. Do you agree?

JB: The Buddha didn’t lay out a single path for everyone to follow. Instead, he created three paths according to people’s needs, capabilities and karma. Each path approaches the Three Poisons [i.e., ignorance, desire and hatred] differently. The Theravada path avoids the poison. Mahayana takes an antidote. But Vajrayana distills the poison to its pure essence, leading us to our Buddha Nature. Vajrayana [or Tibetan] Buddhism is so efficient that one can attain enlightenment in a single lifetime.

RE: Did Milarepa [a famous murderer-turned-yogi] follow Vajrayana?

JB: He did. Milarepa understood emptiness, which enabled him to cultivate compassion in a relatively short amount of time.

Usually, the process takes years—or lifetimes—to master, whether by studying text or modeling behavior. I learned a lot by watching my teacher. I loved how he recited prayers in retreat and behaved with his vajra brothers and sisters.

Accomplishment doesn’t come from holding your breath or doing advanced poses; it comes from lessons that are showered upon you over time. My aspiration is Bodhicitta—awakening the mind of enlightenment for the benefit of others.

BTV: You’ve said that Thubten Yeshe [a Tibetan lama who co-founded Kopan Monastery in Nepal] had a big impact on you. Is that right?

JB: He woke me up, so to speak. Lama Yeshe was a principal figure in the transmission of tummo and tantra [which emphasizes spiritual technology and contemplative arts]. He advocated Je Tsongkhapa’s three principal aspects of the path—Renunciation, Bodhicitta and Shunyata, which is emptiness. I was 13 when I first saw a photograph of Lama Yeshe in a book my father gave me. It was like electricity shot through my body.

When I later went looking for a tummo teacher, I wanted the best—not just in the United States, but in the world. It took me a decade to find him.

RE: By “him,” do you mean Pema Dorje?

JB: Yes. We met at a weekend yoga retreat in New York. The main reason it took so long for us to come together was that I had lacked merit. I also wasn’t clear on what I wanted from him, nor did I understand what it fully meant to be his student. I went to Pema Dorje Rinpoche looking for advanced yogic practices. What I got in return was something else, something far more important.

Although he’s passed away, I’ve never stopped practicing—and teaching—what Lama Pema Dorje shared with me about Buddhist vehicles to liberation. [Much of Bae’s teachings references Pema Dorje’s commentary on the Padampa Sangye classic, Lion of Siddhas: The Hundred Verses of Advice.] I still feel him between my ears. I cry almost every time I teach and practice because I feel like he’s inside me. Practicing is a way to remember the kindness and love of one’s preceptors.

RE: Speaking of lineage, Pema Dorje’s ancestors can be traced back to Milarepa’s paternal line, almost a thousand years ago. What can ordinary householders learn from such exalted company?

JB: Teaching meets us where we’re at. Practicing dharma requires commitment, so we must approach it in context of our work and family lives. We should honor who we are and where we’re at in our spiritual journey, instead of suppressing or being ashamed of it. There’s no one-size-fits-all. That’s the essence of dharma—it’s beautiful. And it’s uniquely yours.